UTCTF 2019 - Crackme

Zander Work

Tags

This was a 1200 point reversing challenge (tied for highest point value in the category). Here’s the description:

This what we see when we run the binary:

$ ./crackme

Please enter the correct password.

>pls

Incorrect password. utflag{wrong_password_btw_this_is_not_the_flag_and_if_you_submit_this_i_will_judge_you}

Let’s take a look at the code in IDA Pro:

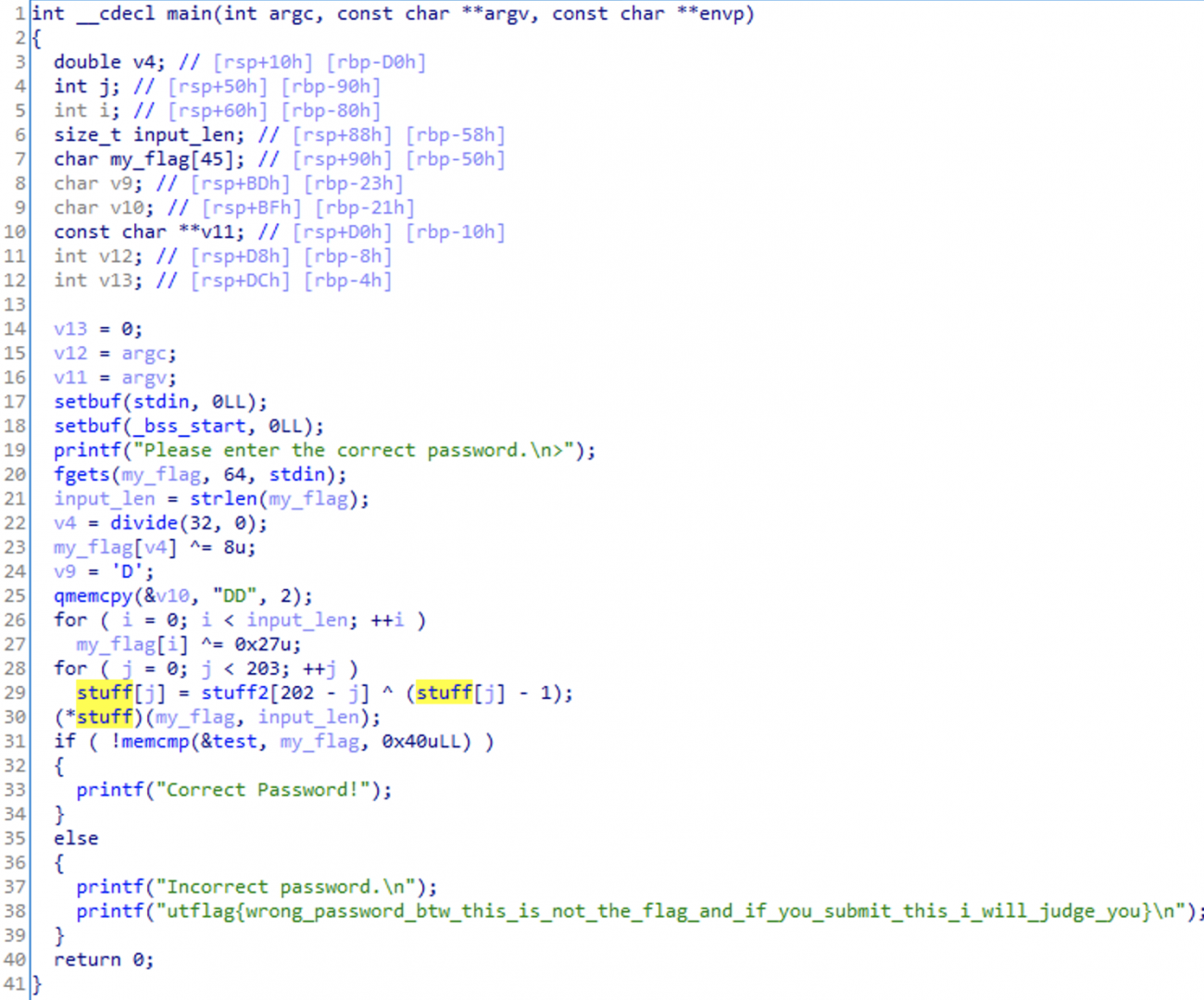

Here’s what the decompilation shows:

- Read in 64 bytes from stdin

- Call divide(32, 0), and save the return value to v4

- xor our input at index v4 with 8

- Replace a few characters of our input with ‘D’

- xor each character in our input with 0x27

Now we see “stuff[j] = stuff2[202 – j] ^ (stuff[j] – 1);”. stuff and stuff2 live in the .data section (along with test). The loop applies that operation to each of the first 202 bytes of stuff (there are some null bytes afterwards for padding), and then calls it. This is quite cool, and not something I have seen in a reversing challenge before. The binary is modifying it’s own data to create a new function, and then execute it to add additional layers of obfuscation.

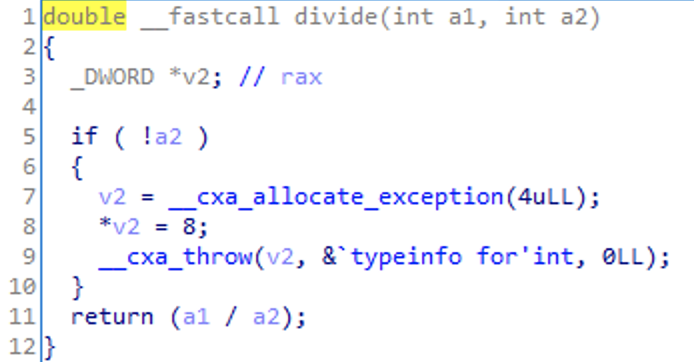

Before I start working through that obfuscated function, I took a look at divide():

Based on the function call “divide(32, 0)”, it does indeed do a divide by zero, which throws an exception, further messing with our debugging and analysis. I ended up just skipping it and not worrying about it, which worked out in the end.

In order to analyze that obfuscated function in .data, I needed to do a few things:

Extract stuff and stuff2 from the binary

Write a program to apply the deobfuscation to stuff

Disassemble/decompile the resulting function for analysis

I used gdb to get extract the two variables. Here’s what that looks like for stuff:

$ gdb crackme

Reading symbols from crackme…(no debugging symbols found)…done.

gdb-peda$ x/52x &stuff

0x602090 : 0xed592513 0x908d3643 0x6bd01bc6 0xc3112c86

0x6020a0 : 0xb55cd9d3 0x92a40224 0x4566fb3a 0x74a5731d

0x6020b0 : 0xccea82e8 0xd125398a 0x2a5105e7 0x67b7a235

0x6020c0 : 0x99a1886b 0xf224a523 0x06eb4f61 0x816685bd

0x6020d0 : 0xd979c55b 0x841c39e4 0xb7c6288c 0xc599716e

0x6020e0 : 0xc550b65d 0xed393d86 0xc417dd7a 0x96681e07

0x6020f0 : 0x1ae03766 0x52637a30 0x05718f9f 0x8c4c3973

0x602100 : 0xcc581405 0xa2db617f 0x9993db2b 0xc7ebb606

0x602110 : 0x182b63b3 0xaa4e0a50 0x8192d259 0x7ae97ae7

0x602120 : 0xe479bea9 0x53e79c45 0x9c26894b 0x9ea75bf8

0x602130 : 0xadf5e45d 0x41aede98 0xd230dd97 0xfb81fd17

0x602140 : 0x4ac0d10a 0x735f3ee8 0xfcc0a13c 0x839c7ffd

0x602150 : 0xff03fb9b 0x4be73391 0x00c93d31 0x00000000

gdb-peda$ dump memory stuff.bin 0x602090 (0x602090 + 204)

This writes 204 bytes after 0x602090 to stuff.bin. I did the same thing for stuff2, and then wrote a C program to apply the xor operation and dump it back to disk. You can see the program here.

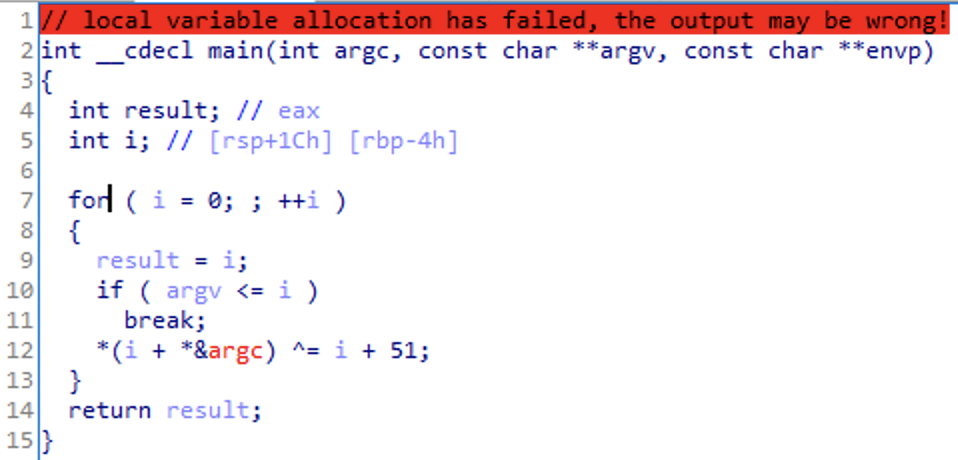

With that in hand, we were able to pull out a function that I wanted to decompile. While I would not recommend doing it this way, I wrote a Python program (which you can see here) that replaced the main() function of the original binary with the new function and dumped it to a new binary so I could load it into IDA:

While IDA didn’t do a great job parsing the function since it thought it was main, it showed us the logic. The function applies an xor to each byte with the loop counter plus 51, simple enough.

At this point, I had enough information to write another Python script (which you can see here) to build the password based on the test value it gets compared against. I extracted test using the same method I showed above for stuff, and did the following things:

- Read in the test data

- Undo the deobfuscated stuff function

- Undo the 0x27 xor

That script provided this output:

$ ./solve.py

'1_hav3_1nf0rmat10n_that_w1ll_lead_t0_th3_arr3st\x1b0f_cspp3rstick6U'

There are some bad characters in here, which is due to some extra xors I didn’t want to mess with, so I just guessed and got lucky on what the password was supposed to be:

$ ./crackme

Please enter the correct password.

>1_hav3_1nf0rmat10n_that_w1ll_lead_t0_th3_arr3st_0f_c0pp3rstick6

Correct Password!

The flag is utflag{1_hav3_1nf0rmat10n_that_w1ll_lead_t0_th3_arr3st_0f_c0pp3rstick6}.

Some extra info:

If you wanted to analyze this dynamically, you would have had some trouble:

$ gdb crackme

Reading symbols from crackme…(no debugging symbols found)…done.

gdb-peda$ b *main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x400af0

gdb-peda$ r

Starting program: /mnt/hgfs/sec/utctf19/crackme/crackme

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

[Inferior 1 (process 5869) exited with code 01]

Warning: not running or target is remote

gdb-peda$

Why doesn’t our breakpoint get hit?

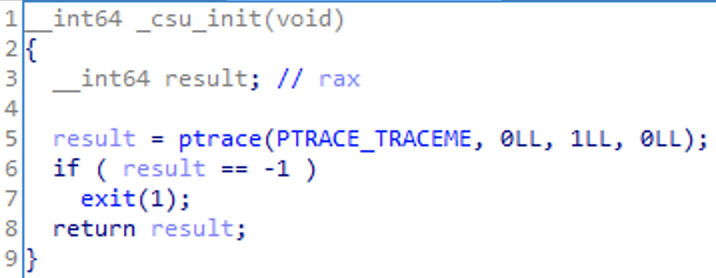

This is due to a sneaky move by the challenge author by putting a ptrace() call in a function called _csu_init(), which causes debugging to be unsuccessful. If there is more than one trace applied to the program, it exits:

You can patch out the ptrace call with nops, which would allow you to dynamically analyze this. I patched the binary while I was working on the challenge, but ended up just doing it statically.